Driving a Smarter Future

Newsletter

IRENA analysis explores the potential and impact of smart charging electric vehicles on the energy transition

Today the average car runs on fossil fuels, but growing pressure for climate action, falling battery costs, and concerns about air pollution in cities, has given life to the once “over-priced” and neglected electric vehicle.

With many new electric vehicles (EV) now out-performing their fossil-powered counterparts’ capabilities on the road, energy planners are looking to bring innovation to the garage — 95% of a car’s time is spent parked. The result is that with careful planning and the right infrastructure in place, parked and plugged-in EVs could be the battery banks of the future, stabilising electric grids powered by wind and solar energy.

An electric car charging station powered by solar PV

“EVs at scale can create vast electricity storage capacity, but if everyone simultaneously charges their cars in the morning or evening, electricity networks can become stressed. The timing of charging is therefore critical. ‘Smart charging’, which both charges vehicles and supports the grid, unlocks a virtuous circle in which renewable energy makes transport cleaner and EVs support larger shares of renewables,” says Dolf Gielen, Director of IRENA’s Innovation and Technology Centre.

Looking at real examples, a new report from IRENA, Innovation Outlook: smart charging for electric vehicles, guides countries on how to exploit the complementarity potential between renewable electricity and EVs. It provides a guideline for policymakers on implementing an energy transition strategy that makes the most out of EVs.

Smart implementation

Smart charging means adapting the charging cycle of EVs to both the conditions of the power system and the needs of vehicle users. “Smart charging is one of the innovations IRENA is closely following that presents multiple benefits. By decreasing EV-charging-stress on the grid, smart charging can make electricity systems more flexible for renewable energy integration, and provides a low-carbon electricity option to address the transport sector, all while meeting mobility needs,” says Gielen.

The rapid uptake of EVs around the world, means smart charging could save billions of dollars in grid investments needed to meet EV loads in a controlled manner. For example, the distribution system operator in Hamburg — Stromnetz Hamburg — is testing a smart charging system that uses digital technologies that control the charging of vehicles based on systems and customers’ requirements. When fully implemented, this would reduce the need for grid investments in the city due to the load of charging EVs by 90%.

IRENA’s analysis indicates that if most of the passenger vehicles sold from 2040 onwards were electric, more than 1 billion EVs could be on the road by 2050 — up from around 6 million today —dwarfing stationary battery capacity. Projections suggest that in 2050, around 14 terra-watt hours (TWh) of EV batteries could be available to provide grid services, compared to just 9 TWh of stationary batteries.

The implementation of smart charging systems ranges from basic to advanced, says Francisco Boshell, an IRENA analyst monitoring the development and implementation of EV strategies around the world. “The simplest approaches encourage consumers to defer their charging from peak to off-peak periods. More advanced approaches using digital technology (PDF), such as ‘direct control mechanisms’ may in the near future serve the electricity system by delivering close-to real-time energy balancing and ancillary services,” explains Boshell.

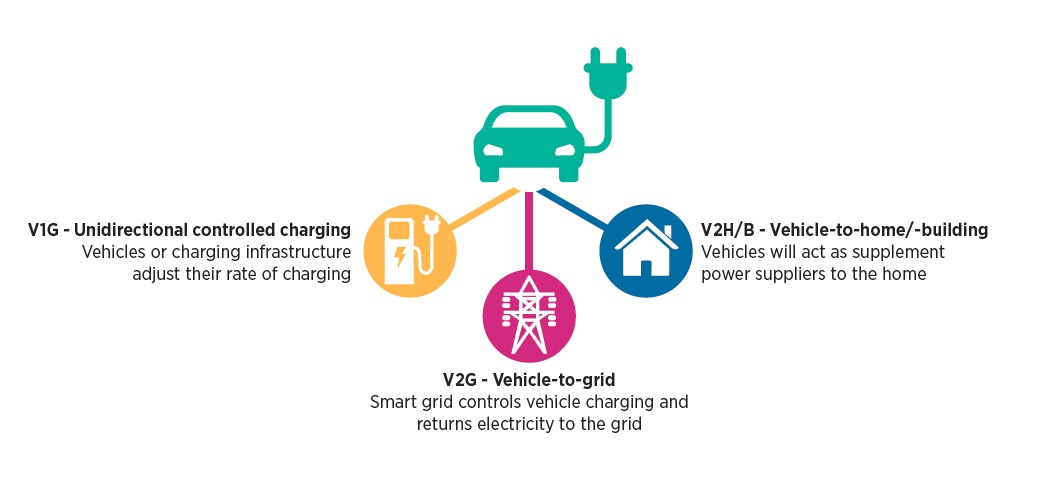

Advanced forms of smart charging

An advanced smart charging approach, called Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G), allows EVs not to just withdraw electricity from the grid, but to also inject electricity back to the grid. V2G technology may create a business case for car owners, via aggregators (PDF), to provide ancillary services to the grid. However, to be attractive for car owners, smart charging must satisfy the mobility needs, meaning cars should be charged when needed, at the lowest cost, and owners should possibly be remunerated for providing services to the grid. Policy instruments, such as rebates for the installation of smart charging points as well as time-of-use tariffs (PDF), may incentivise a wide deployment of smart charging.

“We’ve seen this tested in the UK, Netherlands and Denmark,” Boshell says. “For example, since 2016, Nissan, Enel and Nuvve have partnered and worked on an energy management solution that allows vehicle owners and energy users to operate as individual energy hubs. Their two pilot projects in Denmark and the UK have allowed owners of Nissan EVs to earn money by sending power to the grid through Enel’s bidirectional chargers.”

Perfect solution?

While EVs have a lot to offer towards accelerating variable renewable energy deployment, their uptake also brings technical challenges that need to be overcome.

IRENA analysis suggests uncontrolled and simultaneous charging of EVs could significantly increase congestion in power systems and peak load. Resulting in limitations to increase the share of solar PV and wind in power systems, and the need for additional investment costs in electrical infrastructure in form of replacing and additional cables, transformers, switchgears, etc., respectively.

An increase in autonomous and ‘mobility-as-a-service’ driving — i.e. innovations for car-sharing or those that would allow your car to taxi strangers when you are not using it — could disrupt the potential availability of grid-stabilising plugged-in EVs, as batteries will be connected and available to the grid less often.

Impact of charging according to type

It has also become clear that fast and ultra-fast charging are a priority for the mobility sector, however, slow charging is actually better suited for smart charging, as batteries are connected and available to the grid longer. For slow charging, locating charging infrastructure at home and at the workplace is critical, an aspect to be considered during infrastructure planning. Fast and ultra-fast charging may increase the peak demand stress on local grids. Solutions such as battery swapping, charging stations with buffer storage, and night EV fleet charging, might become necessary, in combination with fast and ultra-fast charging, to avoid high infrastructure investments.

To learn more about smart charging, read IRENA’s Innovation Outlook: smart charging for electric vehicles. The report explores the degree of complementarity potential between variable renewable energy sources and EVs, and considers how this potential could be tapped through smart charging between now and mid-century, and the possible impact of the expected mobility disruptions in the coming two to three decades.